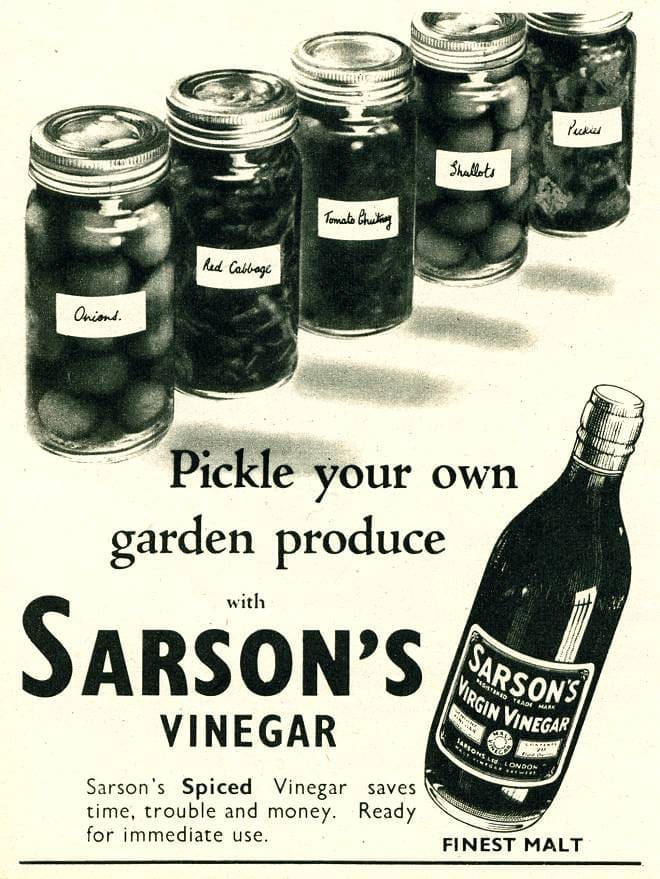

Vinegar making was more of an art than a science.

These not very comforting words were uttered to me through an expanding cloud of acrid pipe smoke by old Mr Houghton.

It was 1970, and two weeks earlier I’d seen an advert in the local paper for a career in vinegar brewing. After writing my application and attending a Saturday morning interview at the Sarson’s factory in Middleton, Manchester, I was offered the job there and then.

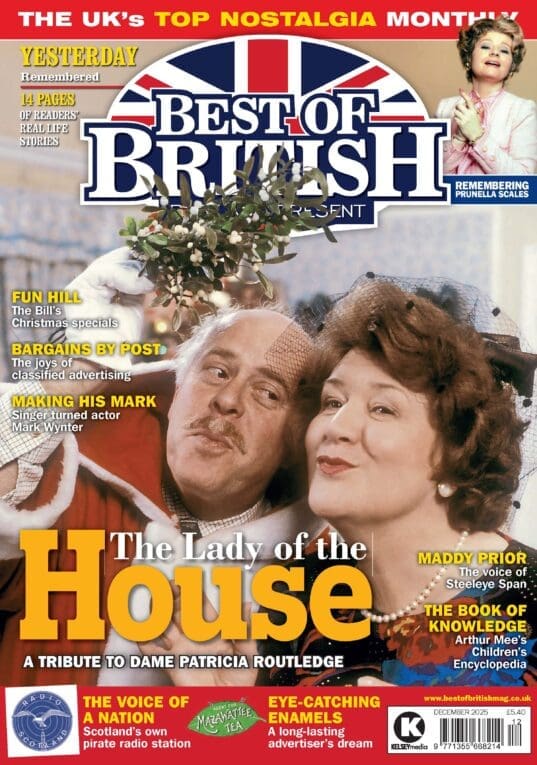

Enjoy more Best of British Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

In the first week I was taken under the wing of this kindly looking gentleman who relished the opportunity to show an eager young lad all he knew. He had previously been a factory manager and was now helping the new management establish the operation as his swansong. The current manager had little choice but to suffer him and his unwanted advice, so was happy to leave him roaming free in the laboratory, away from most of the workforce.

He produced an ancient but impressive-looking microscope out of an old cupboard. I was instructed to go into the brewery, which was full of wooden vats of many different sizes made of oak, some of them over a hundred years old, and bring back a sample of unfiltered vinegar. He spread a sample of the liquid onto a slide and told me to look down the microscope. I jumped out of my skin. Massive serpents were writhing about in there! He jocularly explained that they were vinegar eels, common and completely harmless. They would later be filtered out.

“Where do they come from?” I enquired. “Nobody knows,” he replied. From this and other queries I threw at this father figure, I slowly began to suspect that vinegar brewing was less of a science than was made out. This was drastically confirmed when Jenks came back.

Throughout the first week, Old Houghton, as he was referred to, had often warned me about the slapdash approach of young Jenks (he was 35 years old), who would be my direct boss.

Jenks cruised into the office an hour after I’d started and the first impression was of a medallion man with a large moustache. After introductions I was left alone with him. He told me all about Mr Houghton’s history. They didn’t use first names when talking to each other; it was Jenks or Mr Houghton. Things were very formal, but I think they were embarrassed that they both happened to be called Ron.

The next day I was to go to the factory with Jenks to learn about brewing. This seemed to consist of putting on a white coat and turning a few handles after a muscled ex-serviceman, called Tom, had done all the hard work milling, setting up valves and pipes, and cleaning.

“You open that valve a bit and let the hot water mix with the grain,” he said.

“How do I know how much to open the valve?”

“Until it sounds right, plopping into the mash tun.”

The mash tun was a large round vessel with slits in the base to allow liquid to drain through. When this was done we went for breakfast and returned half an hour later. Various valves were opened and closed and Tom was trusted to keep things going. We would appear every hour or so to monitor proceedings.

As this was a career, you were expected to be flexible. One day I was told I’d be doing the wages next week as the clerk was going on holiday. After being shown the hidden mysteries of ledgers and tax tables, I was off to the bank to collect the wage money. This was inserted in brown envelopes and handed out on Friday. I still shudder to think how all those poor workers were depending on me to deduct the right amount of income tax.

The first Christmas was a surprise. We brewers got a free fresh turkey from the grain merchants. This let skeletons out of cupboards, as in hushed tones, Jenks told me that Old Houghton lived with Miss Cressy, a director of the merchants.

It was a different era then. Management were technical and didn’t bother about where the money was made or lost. It may be more efficient these days but performance indicators and metal tanks can’t compete with the beauty of handmade wooden vats and having time to contemplate and experiment.

Geoff Keeling

This article appeared in the May 2010 issue of Best of British.