A childhood spent in a hospital bed.

My father was a labourer on a dairy farm in the 1930s, when it was not unusual for cows to be carriers of tuberculosis. This, together with bad housing, was why I contracted tuberculosis of the spine at the age of two.

My parents knew something was wrong with me and took me to several doctors, none of whom could diagnose my problem. Eventually they managed to get an appointment with Dr Pain (an unfortunate name for a doctor). An orthopaedic specialist at Leeds Infirmary, he diagnosed the problem immediately.

Enjoy more Best of British Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

After spending some months for tests in Leeds Infirmary, I was admitted to the Marguerite Hepton Hospital in Thorpe Arch, Yorkshire, in July, 1937. I stayed there for the next five years.

It was a small hospital with just 80 long-term patients, aged from a few months to 14. There were 37 nurses and no resident doctors, so the local GP was called in if a patient was ill. The nurses had no morning drugs to dispense and no dressings to change so their daily routine was mostly housekeeping. This included cutting the patients’ hair, which they were not very good at.

For me, life in hospital wasn’t dull. I knew nothing else – I had never been to school, travelled on a bus, ridden in a car, ridden a bicycle, or played games with other children. To me hospital life was normal.

Our education was not neglected and we had an elderly female teacher who came each weekday to the hospital. As well as arithmetic, reading and writing, we were taught embroidery and knitting. We spent many hours knitting huge woollen stockings for sailors with very thick and oily wool. They were called sea boot stockings and were issued to sailors on the winter convoys going to Russia. We also were taught how to make nets, but I never knew why.

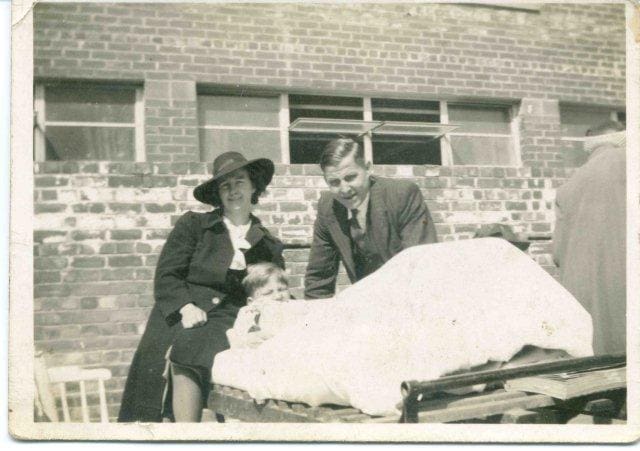

Parents were allowed to visit for only one hour each month. Towards the end of my stay in hospital in 1942, this was extended to one hour a fortnight. But if visiting day fell on certain dates in a month, for example on the first of the month, it was cancelled arbitrarily with no explanation. Letters notified our parents only the day before they were due to visit.

The main treatment for tuberculosis was plenty of fresh air. Our hospital beds were simple wooden affairs, with large wheels so they could be moved easily. We spent almost all of each day outside, often regardless of the weather. Each bed had a vertical post at each end with a crosspiece between, so that a tarpaulin could be laid over us in wet or snowy weather. With makeshift walls on three sides, the fourth was completely open to the elements.

It was a long, hot summer in 1940, and as our beds were always placed outdoors, we frequently could see the dog fights between the aeroplanes above us. The German Air Force bombed the nearby munitions factory several times during the war, but did very little damage as much of the site was underground. One day, all the patients’ beds were outside as normal. There was an air raid on the factory but some of the bombs overshot, one of which landed in the hospital grounds. It exploded on a grassy area midway between the nurses’ quarters and the wards, and was quickly followed by a number of German aircraft flying very low, with the more explosions very quickly afterwards. Although the hospital was undamaged and no one was hurt, it was extremely frightening for everyone.

We children had no notion of the death and injuries sustained by pilots of both sides at this time. Neither had we any idea of the hardships of the civilian population. Food rationing and other difficulties our parents endured were totally unknown to us.

Dental hygiene in the hospital was a problem. No facilities were provided for us to clean our teeth daily, so problems often arose. A visiting dentist came to the hospital at intervals for inspections. All patients needing treatment were then taken to the operating theatre. The dentist had to bring all his equipment with him, which included a pedal-operated drill. One of the nurses would be co-opted to pedal, with the doctors continually telling her to pedal faster. Dental anaesthetics must have been unobtainable as I recall having extractions without them. I have a vivid memory of being in the operating theatre spitting blood and bits of tooth whilst bawling loudly. Since that experience, though I can face the prospect of a major operation without difficulty, I cannot even enter a dental surgery without feeling sick.

In 1941, I had a spinal fusion operation to cure my tuberculosis. Sores, which stank terribly, were an inevitable result of being encased in plaster for many months. The treatment for plaster sores consisted of first cutting the plaster off using heavy shears, which dug into one. Then the sores were treated with methylated spirits, which was extremely painful and smelly. After treatment, the patient was encased in a new plaster cast and the whole cycle would start again.

In September, 1942, I was discharged from hospital, but first I had to learn to walk. As I had been lying horizontally for all of my life, I had to get accustomed to being upright. Each morning I was placed in a wooden frame, which then was fastened to the foot of the bed to hold it upright. After a few days of this treatment, I was taught to walk. One of the nurses stood me on her feet and showed me how it was done.

Then, at the age of ten, I finally was discharged from hospital.

Harry Dodgson

This article appeared in the May 2010 issue of Best of British.