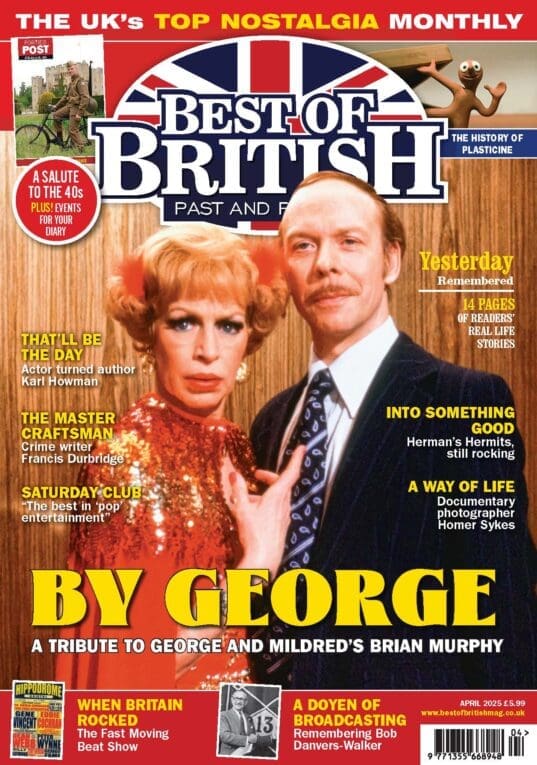

Life with wartime shortages.

As a schoolboy, I was blissfully unaware of the significance of July 3rd, 1954; the day that marked the end of food rationing in Britain. For my parents it meant the end of 14 years of making do, or even doing without.

The first item to be rationed was petrol in 1939, but unlike for later generations, it made little difference for the majority of people in this country in those days anyway. They could ignore that rationing. Not so the following January, when bacon, butter and sugar were rationed. How my mother loved her sweet tea. But when you only had three ounces, and that had to last a whole week, unsweetened tea had to be persevered with.

Enjoy more Best of British Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Worse was to come two months later, when tea was rationed to two ounces a week. Was nothing sacred? But sacrifices had to be made, for the country was fighting for its life. By attacking our shipping, the enemy was trying to starve us into submission. Jam and cheese went on to the list the following year.

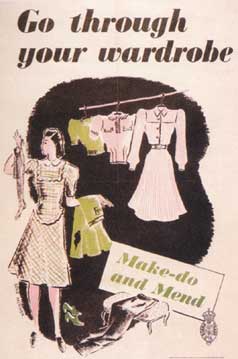

Clothes rationing was introduced in June, 1941, with points coupons. You could, for example, get a new dress for seven points. The allowance would allow one new outfit per year, but you could buy second-hand clothes at a government fixed price. The same month, one egg a week became the allowance. The alternative of one packet of dried eggs (said to make the equivalent of 12 fresh eggs) was not always popular. Vegetarians were allowed two eggs, as well as extra cheese, but of course they gave up their meat allowance.

Keeping the home fires burning would be harder after the government decided to ration coal in July, 1941, and in the following year, gas and electricity supplies were rationed. The soap allowance, both household and personal, was one pound, but had to last a whole month. I can’t imagine that stopping my mother from looking after her family and her house, and keeping things as clean as possible.

There were, of course, many other rationed foodstuffs that dictated what my mother could put on the dining room table. But like countless others, she made do. It became a way of life, especially when there were shortages. Because my sister and I were under 14 years of age, my mother was exempt from working in the local munitions factory or shops, and could devote time and energy to making sure there would always be something on the table.

Just because you had coupons for something didn’t mean they were available at the shops. And so, on the barest rumour that a shop had a new delivery of, say, butter or meat, my mother would rush out with her ration book and purse and join the assembling queue outside the shop – long lines of patiently waiting people out in all weathers, just on the off chance there would be some pork chops or sausages left when they finally got to the counter (how my father loved sausages for his breakfast). Many shops opened for only two or three days a week because of these shortages.

My mother told me that there were different kinds of ration books with tokens that could be exchanged for goods. She told me of a young unmarried woman living next door who was issued with a green ration book. As green books were only issued to expectant mothers, who needed extra tokens, it created a bit of a scandal in the street.

Growing food in gardens or any patch of land was for many people the only way to supplement their diet. My father, who worked at the same local munitions factory as my mother, spent most of his free time tending to the vegetables growing in his mother’s small front garden. Our small terraced house had neither garden nor space for one. And so he had to dig up the grass and bushes to make way for potatoes, cabbage and whatever else would grow in its poorly nourished soil.

I wonder what my parents would have thought if they ever knew the story of Winston Churchill asking to see an example of typical rations, and being shown a life-size wooden mock-up of the rations. He said with satisfaction: ‘All in all, a fine meal. A fine meal’. When told those rations had to last for a week, not for a single meal, as he had thought, Churchill thundered out: ‘Then the British people are starving. Something must be done.’

I am sure it was close run at times, but somehow my parents survived and brought up me and my older sister. Indeed, we are told the wartime diets were some of the healthiest in our history. Healthy, yes, but my mother told me it was a constant battle to make the relatively dull food interesting.

One of the few things that weren’t rationed was fish and chips. This was a sensible, morale boosting, decision by the government, ensuring that a filling warm meal could be available most of the time for people. After all, we were surrounded by seas full of fish and we could always grow potatoes. My father told me I loved sucking on the scraps of fish batter as a treat.

Bread was not rationed during the war, but it was in later years, from 1946. My mother would have been so glad that, two years later, flour came off the list. Now she could bake bread in her oven. Other foodstuffs came slowly off rationing: tinned and dried fruit, mincemeat, chocolate biscuits, tea, sugar and much else. I suppose the best day for a young schoolboy was when sugar and sweets were once again freely available. I’m sure I ate a lot of sweets that day!

Clothes rationing had ended in 1949. No more sewing patches in worn-out jumpers, cardigans and jackets. Women no longer had to dying their legs with gravy browning, and make a mock stocking seam with eyeliner.

Most ration books would have been burnt ceremoniously, and with glee, on bonfires burning on De-ration Day. There would be others, I suppose, like my mother, who kept one as a reminder of those awful days of doing without.

Anthony de Wolf

This article appeared in the July 2009 issue of Best of British.